If you have not watched any of our YouTube videos at our channel Deere Family Homes, we encourage you to check out the April 2022 video. The video features the story of one painting hanging in the Deere-Wiman House. The painting’s artist is Alexander Harmer.

We are lucky to have four paintings in our collection that were created by Harmer. It made sense for us to learn more about Harmer and see if we could determine why we have so many paintings from one artist. I love all four pieces and wanted to know more about the artist and determine if there was a connection to the family. Three of the paintings hang in the Deere-Wiman House and one at Butterworth Center. So, it was not just one family member that took an interest in his work.

Did any of the family know Alexander Harmer? We wish we knew. It is possible since Harmer’s life in Santa Barbara does overlap with the Butterworth and Wiman families. Or maybe the family did not know Harmer but was drawn to his art and purchased pieces through art dealers.

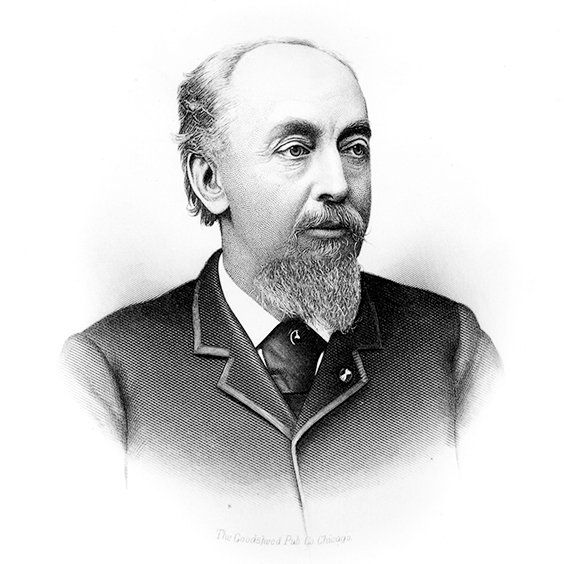

Alexander Francis Harmer was born in 1856, in Newark, New Jersey. One source I read said that he sold his first work at the age of 11 for $2. Then at the age of 16, he lied about his age and joined the United States Army. He was stationed in California, which I think is the time period his artistic interests changed. He turned towards painting and illustrating the Apache Nation. The year would have been 1872, and the US Army would have had a large presence in the West with the enforcement of federal Indian policy (which consisted of allotment of land and assimilation.)

After just one year, Harmer asked for a discharge and left the military. He worked as a photographer’s assistant until he was able to enroll in art school. He studied art under Thomas Eakins and Thomas Anshutz at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art. In 1881, he re-enlisted in the Army and headed to his assignment at Fort Apache, Arizona. Harmer probably saw the Army as a cheap way of traveling West to continue his interest in the American West and the Apache Indians. During this enlistment, he was able to serve in an Army division assigned to pursue Geronimo. His studies of Indian life created an invaluable record. Harmer then returned to the academy in Pennsylvania where he turned his sketches of the Apache Nation into illustrations for Harper’s Weekly.

Alexander Harmer died on January 10, 1925, supposedly while admiring the sunset from his backyard. This was just six months before the Santa Barbara earthquake, which left the Harmers' adobes in ruins.

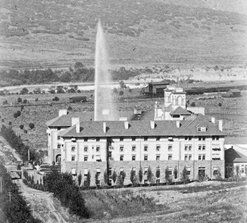

Click here to view a new video on our YouTube Channel featuring the Swimming Pool built in 1917 on the Deere-Wiman House grounds. https://youtu.be/NgV6XUEkrLs