Charles H. Deere commissioned Hillcrest as a wedding gift for his daughter, Katherine Deere Butterworth, and son-in-law William Butterworth following their marriage in 1892. The house was constructed between 1892-1893. During this time, the newly married Butterworths resided with the Deeres at Overlook, Katherine’s childhood home.

As the original plans for the house have not been located, it is not known for certain which architect or builder is responsible for its initial design. Merton Yale Cady has traditionally been considered the most likely candidate. This is based on his relationship to the Deere family through his marriage to Alice Lamb Deere (making him Charles H. Deere’s brother-in-law and Katherine’s uncle) and Deere and Company, where Cady served as a kind of project manager for the company’s building projects. Cady is also the only architect listed in an 1892 Moline city directory.

Although Cady is still considered a possible designer of the house, letters were discovered in the Deere Company Archive which bring another potential candidate to light. J.F. Alexander of Lafayette, Indiana, was in correspondence with Charles H. Deere during 1892 and 1893 with regard to the construction of a house in Moline. Alexander was based in Lafayette but had recently opened a satellite office in Peoria. His expanded practice included his son, James F. Alexander, Jr.

The original Queen Anne style house was significantly smaller than it is today. The home was planned with modern amenities such as gas heating, hot water plumbing, and electricity. In its initial design, the home was entered via either the main entrance at the east elevation or at a small porte-cochere on the north elevation in a configuration not unlike that in the main hall at Overlook/Deere-Wiman House

As the original plans for the house have not been located, it is not known for certain which architect or builder is responsible for its initial design. Merton Yale Cady has traditionally been considered the most likely candidate. This is based on his relationship to the Deere family through his marriage to Alice Lamb Deere (making him Charles H. Deere’s brother-in-law and Katherine’s uncle) and Deere and Company, where Cady served as a kind of project manager for the company’s building projects. Cady is also the only architect listed in an 1892 Moline city directory.

Although Cady is still considered a possible designer of the house, letters were discovered in the Deere Company Archive which bring another potential candidate to light. J.F. Alexander of Lafayette, Indiana, was in correspondence with Charles H. Deere during 1892 and 1893 with regard to the construction of a house in Moline. Alexander was based in Lafayette but had recently opened a satellite office in Peoria. His expanded practice included his son, James F. Alexander, Jr.

The original Queen Anne style house was significantly smaller than it is today. The home was planned with modern amenities such as gas heating, hot water plumbing, and electricity. In its initial design, the home was entered via either the main entrance at the east elevation or at a small porte-cochere on the north elevation in a configuration not unlike that in the main hall at Overlook/Deere-Wiman House

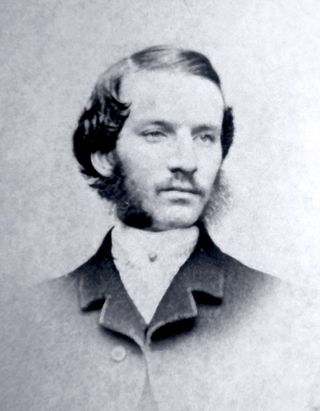

Merton Yale Cady was a well-respected gentleman architect and decorator in Moline, and there has been some speculation that he had a hand in the design on Hillcrest in 1892. Cady was the brother-in-law of Charles H. Deere through his marriage to Alice, the youngest of John Deere’s daughters. He hailed from the East Coast and was a member of the long-established Yale family. Cady’s family members included Elihu Yale, founder of Yale University, and Linus Yale, founder of the Yale Lock Company. Many locks and other door hardware at both the Deere-Wiman House and the Butterworth Center bear the Yale seal, and may have been acquired through Cady’s connection.

Deere and Company archival materials frequently list Cady as an architect or purchasing agent on behalf of Charles H. Deere in the former’s various real estate projects. Further, Cady is credited with designing the Moline City Water Works (now demolished), the Deere Block office and commercial building (also demolished), and the Deere Row apartment building. Starting in 1887, Merton Yale and Alice Deere Cady and their family resided at Red Cliff, John Deere’s former home. Alice inherited Red Cliff upon her father’s death. Cady died in 1900.

Deere and Company archival materials frequently list Cady as an architect or purchasing agent on behalf of Charles H. Deere in the former’s various real estate projects. Further, Cady is credited with designing the Moline City Water Works (now demolished), the Deere Block office and commercial building (also demolished), and the Deere Row apartment building. Starting in 1887, Merton Yale and Alice Deere Cady and their family resided at Red Cliff, John Deere’s former home. Alice inherited Red Cliff upon her father’s death. Cady died in 1900.

Alexander was born in Greene County, Tennessee, the son of William and Maria Henshaw Alexander. Soon after 1850, the Alexander family migrated north into Tippecanoe County Indiana near Romney. In 1857, Maria Alexander died and was buried in the Romney Cemetery. Sometime soon after Maria’s death, William and his younger children migrated west to Harrison County Missouri. Although it is not known where James F. Alexander was during the 1860 census it is probable that he remained in the Tippecanoe County area after his father moved west. He enlisted in the 150th Indiana Infantry from Tippecanoe County in 1863 and mustered out in August 1865. He was married in Decatur, IL in 1868, to Alma Waite. In 1870, he and Alma were residing in Champaign, IL and his employment was listed as a cabinet maker. Their first son William C. Alexander was born in Decatur or Champaign in 1869. His second son James Frank Alexander was born in 1874 and it is believed the family returned to Tippecanoe County soon after that. In 1880, he is listed on the census record as an architect.

Although he primarily worked in Indiana, Alexander was very active in the Western Association of Architects (WAA) and as such made contacts among his colleagues throughout the Midwest. As a member of the WAA, he served on committees within the organization alongside the likes of Dankmar Adler, John Root, and Daniel Burnham, in the years just before the construction of Hillcrest. He continued to serve in the WAA through its consolidation with the American Institute of Architects (AIA) in 1889.

The year 1892 was an eventful one in J.F. Alexander’s professional life. From that year onward, Alexander restyled his firm as J.F. Alexander & Son to include James F. Alexander, Jr., who had recently completed his own architectural training. It is possible that Hillcrest was one of the younger Alexander’s first professional projects, though no existing documentation outlines his precise involvement in the design and construction of the house. The firm also received the commission to build the Indiana State Fairgrounds in Indianapolis in 1892. In October, when Hillcrest’s construction phase was well underway, AIA President Richard Morris Hunt nominated Alexander to several committees within the national organization at the annual meeting in Chicago. Alexander also designed the now-demolished Knights of Pythias Building in Indianapolis in 1905, a stately flatiron building which predated its more renowned New York counterpart (designed by AIA colleague Daniel Burnham) by two years.

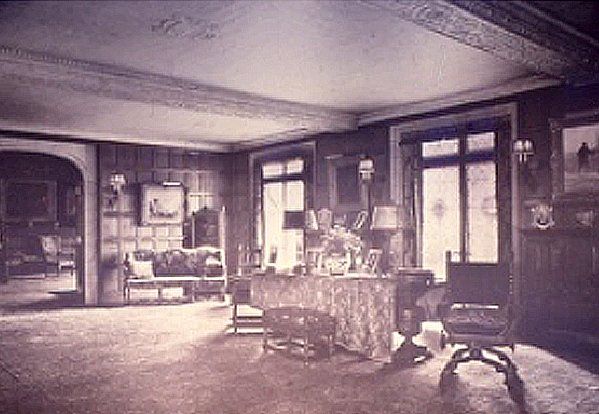

In 1909, the Chicago-based firm of Otis and Clark designed the first major round of alterations for the house. William Butterworth had been named President of Deere and Company in 1907, and it is likely that these renovations were motivated by a desire to update and expand the house. The couple would be expected to host regular social engagements and possibly business meetings. The firm had been working on renovations across the street at Overlook since 1908, and it can be presumed that they received this commission due to familial and logistical proximity. Otis and Clark submitted a number of plans (at least 6) for their Hillcrest renovations before the Butterworths allowed work to move forward.

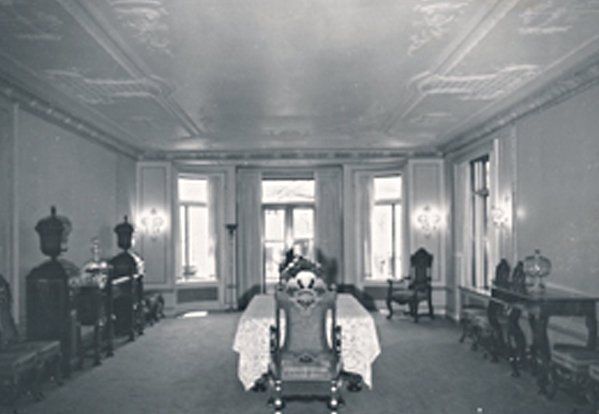

Although the entire house was affected by this alteration scheme, perhaps the most dramatic changes occurred on the first floor. On the south side of the house, the former living and dining rooms were combined into one large living room, and the organ and sunken music room were added at this time, as was the adjacent octagonal south porch. The former butler’s pantry and prep kitchen were then converted into a new dining room, the former main kitchen became the new butler’s pantry, while an addition to the west housed the new larger kitchen and ancillary storage spaces. The service area located in the northwest corner of the house, which had included only a servants’ hall, was altered to include both a sitting room and a dining room. Minimal changes occurred on the second and third floors.

Learn more about Otis and Clark under the Deere-Wiman House timeline .

Some site improvements occurred in 1911, perhaps under Eckerman’s supervision. These included the addition of the underground tunnel and pump room to connect the main house to the greenhouse and garage and extensive reconstruction of the stone walls around the perimeter of the property.

Eckerman again provided designs for the house in 1917. He moved the servant porch from the north side of the house to the west in order to accommodate the new porte-cochere and library (see next section, under Marshal & Fox alterations), and expanded the servant’s sitting room to absorb the former porch. On the second floor, Eckerman oversaw the removal of the mantle and chimney from the south corner of the master bedroom, the installation of new storage cabinetry in Mr. Butterworth’s dressing room, and the mantle and chimney from the former first-floor library into the northeast French Room on the north wall.

Eckerman again provided designs for the house in 1917. He moved the servant porch from the north side of the house to the west in order to accommodate the new porte-cochere and library (see next section, under Marshal & Fox alterations), and expanded the servant’s sitting room to absorb the former porch. On the second floor, Eckerman oversaw the removal of the mantle and chimney from the south corner of the master bedroom, the installation of new storage cabinetry in Mr. Butterworth’s dressing room, and the mantle and chimney from the former first-floor library into the northeast French Room on the north wall.

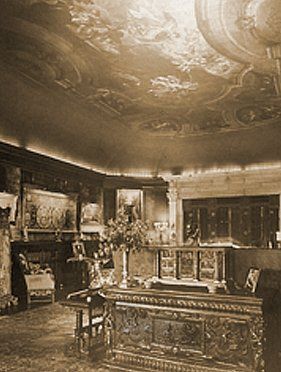

The next alteration program at Hillcrest occurred in 1917 and was designed by the Chicago-based firm of Marshall & Fox, who had apparently submitted plans as early as 1914. These alterations primarily affected the lower level and the first floor. The most significant change occurring at this time was the addition of an octagonal library and porte-cochere off the north elevation. The impetus for this addition was the Butterworths’ acquisition of a 28’x50’ 18th century ceiling fresco by Gaspar Diziani from the Danieli Palace in Venice. This alteration rendered the existing library in the northeast corner of the building redundant, and it was absorbed into the expanded Spanish Gothic Revival style main hall. Stairs leading to the lower level carried the new decorative scheme, designed by the firm of French and Company, to the new porte-cochere vestibule. It is generally accepted that the exterior of the wood framed house was stuccoed at this time. This is supported by the fact that Marshall & Fox were known for their early and widespread adoption of stucco in their designs of the period.

Benjamin H. Marshall was born to a wealthy milling magnate in Chicago, in 1874. Unlike many of his contemporaries who sought recently-legitimized formal architectural education, Marshall entered into an apprenticeship with the firm of Marble and Wilson from 1893 to 1895. Marshall was quickly made a partner in the firm despite his lack of formal training, and opened his own office in 1902 upon his return from a Grand Tour of Europe. In this early phase of his career, Marshall became known primarily as a designer of grand theaters, including the Iroquois Theater in Chicago. Completed in 1903, the Iroquois Theater was destroyed in a notorious and devastating fire in December of that year. Marshall receded from Chicago’s architectural scene until 1905, when he formed a partnership with Charles Eli Fox.

Charles Fox hailed from Reading, Pennsylvania, and attended Lafayette College before receiving his architectural training at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. After graduating from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Fox moved to Chicago and worked in the office of Holabird and Roche from 1891 to 1905 as a steel construction specialist. Unlike Marshall, who tended to design theaters before his partnership with Fox, Fox primarily worked on commercial and office buildings under Holabird and Roche.

When the library addition to Hillcrest began in 1917, Marshall and Fox had established themselves as premier designers of luxury hotels and apartment buildings, including the Blackstone Hotel and Theater (1908) and 1550 North State Parkway (1911). Marshall was credited with introducing the idea of the “French flat,” which distilled all of the domestic luxury of a mansion into a relatively small high-rise apartment; these flats were often marketed as “Mansions in the Sky,” and are now considered the prototype of the modern condominium. The firm was also responsible for a number of high-end residences along Chicago’s North Shore, making them suitable candidates for the Hillcrest renovation. The firm would have been working on one of their most notable designs, the Drake Hotel (1920), while work was underway at Hillcrest.

Charles Fox hailed from Reading, Pennsylvania, and attended Lafayette College before receiving his architectural training at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. After graduating from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Fox moved to Chicago and worked in the office of Holabird and Roche from 1891 to 1905 as a steel construction specialist. Unlike Marshall, who tended to design theaters before his partnership with Fox, Fox primarily worked on commercial and office buildings under Holabird and Roche.

When the library addition to Hillcrest began in 1917, Marshall and Fox had established themselves as premier designers of luxury hotels and apartment buildings, including the Blackstone Hotel and Theater (1908) and 1550 North State Parkway (1911). Marshall was credited with introducing the idea of the “French flat,” which distilled all of the domestic luxury of a mansion into a relatively small high-rise apartment; these flats were often marketed as “Mansions in the Sky,” and are now considered the prototype of the modern condominium. The firm was also responsible for a number of high-end residences along Chicago’s North Shore, making them suitable candidates for the Hillcrest renovation. The firm would have been working on one of their most notable designs, the Drake Hotel (1920), while work was underway at Hillcrest.

Five years later, in 1922, Eckerman removed the French Room fireplace and relocated the room’s entrance to align with the third-floor staircase. This facilitated the conversion of the smaller middle and southeast bedrooms into one larger master bedroom. French and Company, which had designed the interiors for the 1917 Marshall & Fox addition and alterations, also designed the interiors for this 1922 renovation.

In 1925, Eckerman was again summoned to design alterations for the house. These included the southward expansion of the Living Room, Dining Room, and Butler’s Pantry on the first floor. French and Co. again executed the interior decoration scheme, and their Classical Revival living room and Adamesque dining room décor remain in place today. On the second floor, Eckerman added the Green Room guest suite off the west elevation. The silver vault was also added to the storage room on the lower level at this time.

In 1925, Eckerman was again summoned to design alterations for the house. These included the southward expansion of the Living Room, Dining Room, and Butler’s Pantry on the first floor. French and Co. again executed the interior decoration scheme, and their Classical Revival living room and Adamesque dining room décor remain in place today. On the second floor, Eckerman added the Green Room guest suite off the west elevation. The silver vault was also added to the storage room on the lower level at this time.

Portions of this material was taken from the 2016 Historic Structures Review by Sullivan Preservation