The Deere-Wiman House is a unique example of the residential work of William Le Baron Jenney, one of the most prominent architects of the second half of the 19th century.

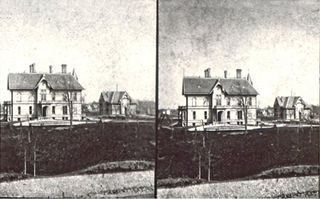

In the early 1870s, Charles Deere, son of John Deere, commissioned William LeBaron Jenney to design a home on the bluffs overlooking downtown Moline, the Mississippi River and most importantly, the John Deere Plow Works. It is believed that the “Swiss Villa” style home (the style Jenney gave his design) was completed by late 1872. Once completed, Charles Deere, his wife Mary, and their two daughters, Anna and Katherine named the home “Overlook”

In the early 1870s, Charles Deere, son of John Deere, commissioned William LeBaron Jenney to design a home on the bluffs overlooking downtown Moline, the Mississippi River and most importantly, the John Deere Plow Works. It is believed that the “Swiss Villa” style home (the style Jenney gave his design) was completed by late 1872. Once completed, Charles Deere, his wife Mary, and their two daughters, Anna and Katherine named the home “Overlook”

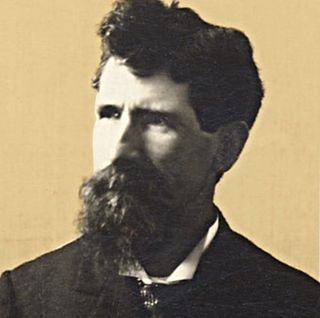

Although history remembers William Le Baron Jenney as one of the Midwest’s most innovative and prolific architects, he was in fact born in Fairhaven, Massachusetts in 1832. He obtained his architectural education from the Ecole Centrale de Paris, graduating in 1856. Jenney found work in 1859 as a consulting railroad engineer in an American-European investment firm. When the Civil War broke out in 1861 he returned to the United States to join the Army. Over the course of the war, Jenney rose to the rank of major (sometimes styling himself “Major Jenney” thereafter) and joined a circle of soldiers-turned-architects following the war that included Frank Furness, Dankmar Adler, and Frederick Law Olmsted.

By 1867, Jenney had established himself in an architectural practice with partner William Bryce Mundie in Chicago; Jenney was also named head of the city’s West Parks System, allowing him to work closely with fellow veteran Olmsted. Olmsted and Jenney went on to design the bucolic suburb of Riverside, Illinois in 1871. Jenney-designed buildings at Riverside were Swiss Gothic in style. It is possible that these buildings influenced the Chalet-style design for Overlook, which would have likely been in the design phase in 1871.

Jenney would go on to teach architecture at the University of Michigan. In addition to his teaching position, Jenney informally served as a mentor and advisor to many of the young architects on his staff. The staff included at various times Louis Sullivan, Daniel Burnham, William Holabird, and Martin Roche, among others. He is perhaps best known for his “invention” of the skyscraper in designing the Home Insurance Building in Chicago in 1884-1885. Jenney’s innovation in this project earned him a place among the most distinguished architects in the country. He continued to design skyscrapers in Chicago throughout his career. Jenney died in Los Angeles, California, in June of 1907, just four months before the death of his one-time patron, Charles H. Deere.

By 1867, Jenney had established himself in an architectural practice with partner William Bryce Mundie in Chicago; Jenney was also named head of the city’s West Parks System, allowing him to work closely with fellow veteran Olmsted. Olmsted and Jenney went on to design the bucolic suburb of Riverside, Illinois in 1871. Jenney-designed buildings at Riverside were Swiss Gothic in style. It is possible that these buildings influenced the Chalet-style design for Overlook, which would have likely been in the design phase in 1871.

Jenney would go on to teach architecture at the University of Michigan. In addition to his teaching position, Jenney informally served as a mentor and advisor to many of the young architects on his staff. The staff included at various times Louis Sullivan, Daniel Burnham, William Holabird, and Martin Roche, among others. He is perhaps best known for his “invention” of the skyscraper in designing the Home Insurance Building in Chicago in 1884-1885. Jenney’s innovation in this project earned him a place among the most distinguished architects in the country. He continued to design skyscrapers in Chicago throughout his career. Jenney died in Los Angeles, California, in June of 1907, just four months before the death of his one-time patron, Charles H. Deere.

In 1899, a fire began on the third floor of Overlook, started by a hot water heater. The resulting damage was primarily to the third floor and roof. It is probable that some interior finishes and furnishings throughout the house, that escaped the fire, were damaged by water and smoke during the fire extinguishing process. Following the fire, several changes occurred at the house. The most conspicuous change occurred at the roof. Jenney’s original steeply-pitched Swiss Gothic roofline was damaged and replaced by a shallower, more contemporary one, enabling the third floor to be built-out to full height.

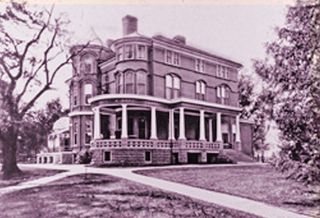

Also, in the 1890s, a wood framed porch positioned off the southeast corner of the house was replaced with what appears to be a domed steel-framed Conservatory.

Also, in the 1890s, a wood framed porch positioned off the southeast corner of the house was replaced with what appears to be a domed steel-framed Conservatory.

The Chicago-based firm of Otis and Clark made alterations to the first, second, and third floors of Overlook, in 1908. Mary Little Dickinson Deere, Charles H. Deere’s widow, appears to have commissioned these alterations. On the first floor, the architects removed the wall dividing the Morning Room and Parlor to create one large Living Room. They also extended the northeast corner of the room to add a rounded window bay. This required the extension of the porch beyond the Living Room. In the Dining Room, the former Conservatory was eliminated to create an open Breakfast Room. To achieve this, Otis and Clark pushed out the former Conservatory’s south wall to form another rounded bay and copied exactly the original Jenney-designed finishes in this one-story space. On the second floor, the northeast bedroom (today called the Rose Room) was expanded to meet the new first-floor round bay, and its fireplace was removed. The fireplace surround from the first floor Morning Room was moved to the northwest bedroom (Green Room). Finally, the northeast bedroom on the third floor was also expanded over the new rounded bay. In their specifications, Otis and Clark noted that they would copy the existing clapboard and mill work on the exterior.

Otis and Clark

Although William A. Otis was born in western New York, he was raised in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and entered the University there in 1874. Otis was enrolled in architecture and civil engineering classes, and his time at the University of Michigan would have coincided with William Le Baron Jenney’s tenure as professor of architecture from 1876 to 1880. Otis left the University in 1878, and briefly worked as a carpenter’s apprentice and draftsman before enrolling in the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris. Shortly after his return from Paris in 1881, Otis began working in Jenney’s Chicago office. By 1887, Otis became a partner in the firm, which was rechristened Jenney and Otis. Just one year later, Otis left Jenney to form his own architectural office in Winnetka, Illinois, and designed a number of churches, libraries, schools, and churches in Chicago and its North Shore suburbs.

Some of Otis’ most noteworthy residential projects were completed in partnership with Edwin H. Clark, a young native Chicagoan. Clark’s father owned the Chicago branch of the Wadsworth Holland Paint Company, and as such, Clark studied chemistry at Yale University in preparation for becoming the company’s technical director. After just three years, Clark contracted lead poisoning and was forced to resign from the paint company. He enrolled in the Armour Institute of Technology (now the Illinois Institute of Technology) in Chicago to study drafting while in recovery, and rededicated himself to a career in architecture. Clark went to work in Otis’ Winnetka office, and became a junior partner in 1908, the same year that the firm designed alterations for Overlook. He remained in partnership with Otis until 1920, at which point Clark opened his own firm. His most enduring work is the Brookfield Zoo (1926-1934), the first American zoo to situate animals in naturalistic habitats rather than behind bars.

Otis and Clark

Although William A. Otis was born in western New York, he was raised in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and entered the University there in 1874. Otis was enrolled in architecture and civil engineering classes, and his time at the University of Michigan would have coincided with William Le Baron Jenney’s tenure as professor of architecture from 1876 to 1880. Otis left the University in 1878, and briefly worked as a carpenter’s apprentice and draftsman before enrolling in the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris. Shortly after his return from Paris in 1881, Otis began working in Jenney’s Chicago office. By 1887, Otis became a partner in the firm, which was rechristened Jenney and Otis. Just one year later, Otis left Jenney to form his own architectural office in Winnetka, Illinois, and designed a number of churches, libraries, schools, and churches in Chicago and its North Shore suburbs.

Some of Otis’ most noteworthy residential projects were completed in partnership with Edwin H. Clark, a young native Chicagoan. Clark’s father owned the Chicago branch of the Wadsworth Holland Paint Company, and as such, Clark studied chemistry at Yale University in preparation for becoming the company’s technical director. After just three years, Clark contracted lead poisoning and was forced to resign from the paint company. He enrolled in the Armour Institute of Technology (now the Illinois Institute of Technology) in Chicago to study drafting while in recovery, and rededicated himself to a career in architecture. Clark went to work in Otis’ Winnetka office, and became a junior partner in 1908, the same year that the firm designed alterations for Overlook. He remained in partnership with Otis until 1920, at which point Clark opened his own firm. His most enduring work is the Brookfield Zoo (1926-1934), the first American zoo to situate animals in naturalistic habitats rather than behind bars.

A Moline native, Oscar Eckerman (known professionally as O.A. Eckerman) was a longtime architect for Deere and Company. He also was engaged to design additions and renovations for private Deere family residences, including both Overlook and Hillcrest. The son of longtime Deere employee John Eckerman, Oscar was raised in Moline before attending Augustana College in Rock Island. Following his undergraduate career, Eckerman undertook his only formal architectural education at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago between 1892 and 1893. Although there is no documentation establishing where Eckerman practiced in the early years of his career, biographer Leonard K. Eaton places him in Chicago and suggests that he may have worked for the noted firm of D.H. Burnham & Company.

Eckerman produced a vigorous and extensive building program for Deere and Company to match Charles H. Deere’s ambitious expansion plans over the course of his 45-year tenure. Eckerman-designed distribution buildings and warehouses were constructed in Atlanta, Bloomington (IL), Chicago, Dallas, Indianapolis, Kansas City (MO), Milwaukee, Minneapolis, Oklahoma, Portland, San Francisco, Spokane, Calgary, Regina, Saskatoon, and Winnipeg. Eckerman’s body of work has drawn comparisons to Albert Kahn, the famed architect for Henry Ford, but he has remained relatively anonymous as a company architect, despite his prolificacy.

Upon his return to Moline in January 1897, Eckerman went to work for Deere and Company as an in-house architect and engineer. At this time, Charles H. Deere’s institution of a company-wide distribution program had taken root, affording Eckerman dozens of opportunities to design additions to existing company buildings, new Deere warehouses and other structures across the country relatively early in his tenure with the company. Some of Eckerman’s more prominent early buildings include the St. Louis (1903-05) and Oklahoma City (1906) warehouses, both of which utilized the heavy timbers and open floorplates characteristic of mill construction. Eckerman proved his virtuosity almost immediately in adopting a new construction trend: reinforced concrete slab. Eckerman’s seemingly utilitarian buildings were not without design. His Classically-inspired white terra cotta door surrounds typically found on Deere buildings from this era, could have provenance in Eckerman’s time in Chicago at the height of the White City/City Beautiful Movement.

Portions of the this material was taken from the 2016 Historic Structures Review by Sullivan Preservation