William Le Baron Jenney

Gretchen Frick Small • January 26, 2021

The discovery of this four-sentence newspaper blurb changed our understanding of Overlook (Deere-Wiman House), the home of Charles H. Deere.

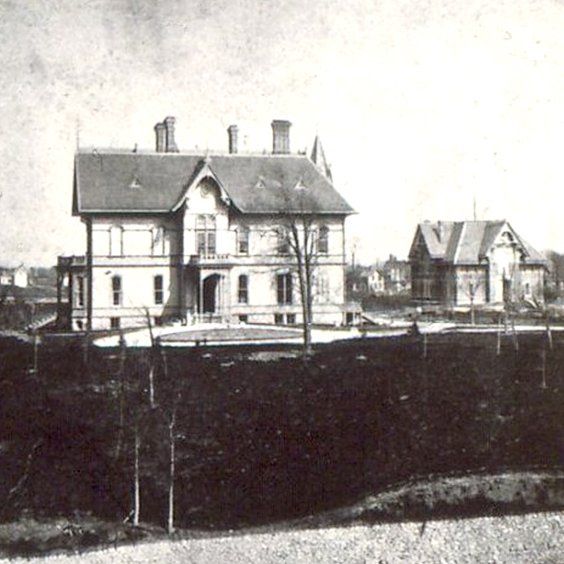

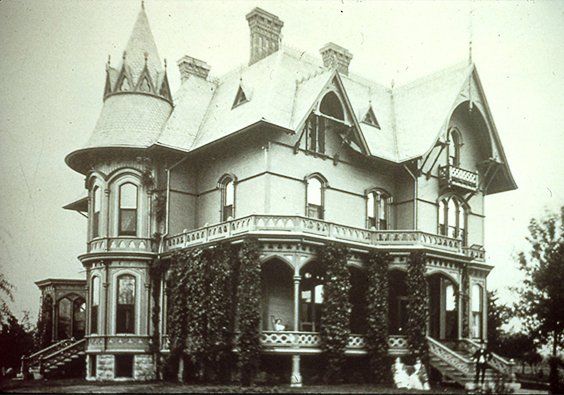

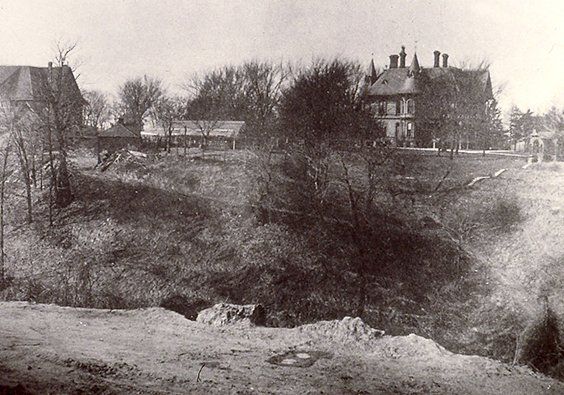

Looking at the west side of the house in 1870s and today (see above), we can see similarities, with some changes including the addition of the stucco. When we view a before and after taken of the house’s north face, we can see that major changes were made (see below).

Even with a wealth of historic photographs, we still did not know the original architect. When was this fact lost to history? Then in the late 1980s, I was digging through the resources at the Rock Island County Historical Society (RICHS) and the Moline Public Library. It was especially helpful that the Society’s research library was just across the street from Deere-Wiman. One valuable resource was the multi volume set, Genealogical abstracts from Rock Island County, Illinois newspapers

compiled by Janet K. Pease. A great source of information before computers! And even more important, the volumes are indexed. I think every historical non-fiction book should have an index.

Pease went through the microfilm of Rock Island County newspapers and listed the newspaper, year and issue date of any article mentioning a name of a person. Can you imagine doing this before computers with just a typewriter? In each volume, the index could be searched for any Deere, Wiman or Butterworth names. After jotting down the newspaper, year and issue date, the next step was to the microfilm reader to pull up the issue and find the article. Imagine my excitement when I read the blurb shown above.

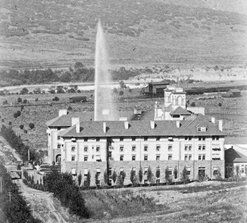

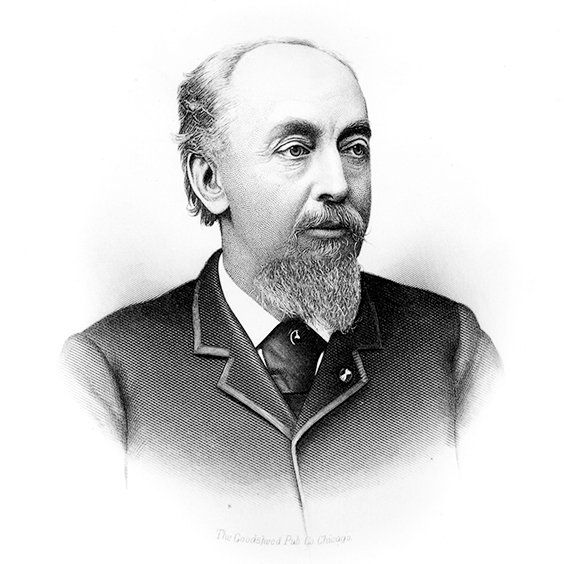

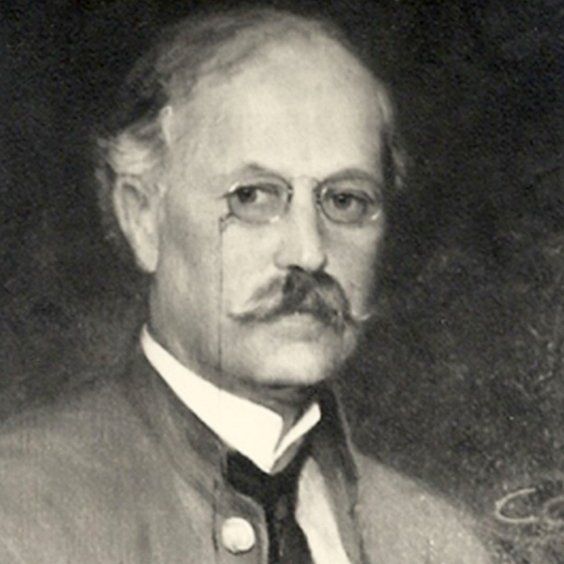

Following the war, he opened his own architectural/engineering firm in Chicago. Just before designing Charles Deere's home, Jenney was heavily involved in the design of Riverside, Illinois. His designs included the Water Tower and several residential buildings. He was known for his use of new technology in his designs.

Today he is best known as the “Father of the Modern Skyscraper,” with his design of the Home Insurance Building in Chicago. Built in 1884-5, the building was torn down in 1931. We also know that he designed landscaping for some of his jobs, including Graceland Cemetery in Chicago.

Today he is best known as the “Father of the Modern Skyscraper,” with his design of the Home Insurance Building in Chicago. Built in 1884-5, the building was torn down in 1931. We also know that he designed landscaping for some of his jobs, including Graceland Cemetery in Chicago.

How did William Le Baron Jenney become Charles Deere’s choice as architect of his new home? We wish we knew.

— Did a Chicago contact of Charles Deere’s suggest Jenney? As a prominent Midwest businessman, Charles Deere would have had many people he could ask for a suggestion.

— Did Mary Deere or her father know of Jenney and suggest him? Mary was from Chicago at the time of her marriage to Charles, in 1862. Her father, Gideon Dickinson, was still living in Chicago in the 1870s.

— Did Charles’ brother-in-law, Merton Yale Cady, suggest Jenney? Cady was an architect and had connections in Chicago. And why didn’t Charles Deere use Cady as an architect? Cady may have felt he didn’t have the expertise to handle the steep terrain of the seven-acre property Charles had chosen for his new home.

— Did Charles hear about Jenney’s work in Riverside, Illinois? Or Jenney’s interest in using the latest technology in his designs?

It could be any of these possibilities or more likely a combination. I like to think that the last suggestion played some part in Charles’ decision. Looking at Jenney's designs in Riverside, Illinois, do show some similarities to Overlook. In addition, Charles was a man who had a deep interest in new technology and innovations. Not only as a businessman, but Charles also had a genuine interest in learning about new technology.

If you have not watched any of our YouTube videos at our channel Deere Family Homes, we encourage you to check out the April 2022 video. The video features the story of one painting hanging in the Deere-Wiman House. The painting’s artist is Alexander Harmer. We are lucky to have four paintings in our collection that were created by Harmer. It made sense for us to learn more about Harmer and see if we could determine why we have so many paintings from one artist. I love all four pieces and wanted to know more about the artist and determine if there was a connection to the family. Three of the paintings hang in the Deere-Wiman House and one at Butterworth Center. So, it was not just one family member that took an interest in his work. We know that William and Anna Wiman moved to Santa Barbara in the 1890s. Then about 1906-07, William and his sons moved back to Moline following Anna’s death. The Santa Barbara house was still owned by the family, and by 1914, Katherine and William Butterworth began to use the house. In addition to the house in Santa Barbara, the Butterworths also owned a residence in the San Marcos Pass area. Mrs. Butterworth continued to spend part of the winter in Santa Barbara until her death in 1953. We also know that Charles Deere Wiman and his family had a home in the area, as early as the 1920s. Did any of the family know Alexander Harmer? We wish we knew. It is possible since Harmer’s life in Santa Barbara does overlap with the Butterworth and Wiman families. Or maybe the family did not know Harmer but was drawn to his art and purchased pieces through art dealers. Alexander Francis Harmer was born in 1856, in Newark, New Jersey. One source I read said that he sold his first work at the age of 11 for $2. Then at the age of 16, he lied about his age and joined the United States Army. He was stationed in California, which I think is the time period his artistic interests changed. He turned towards painting and illustrating the Apache Nation. The year would have been 1872, and the US Army would have had a large presence in the West with the enforcement of federal Indian policy (which consisted of allotment of land and assimilation.) After just one year, Harmer asked for a discharge and left the military. He worked as a photographer’s assistant until he was able to enroll in art school. He studied art under Thomas Eakins and Thomas Anshutz at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art. In 1881, he re-enlisted in the Army and headed to his assignment at Fort Apache, Arizona. Harmer probably saw the Army as a cheap way of traveling West to continue his interest in the American West and the Apache Indians. During this enlistment, he was able to serve in an Army division assigned to pursue Geronimo. His studies of Indian life created an invaluable record. Harmer then returned to the academy in Pennsylvania where he turned his sketches of the Apache Nation into illustrations for Harper’s Weekly. In 1891, Harmer returned to California, and in 1893, he married Felicidad Abadie. The Abadie family was one of the pioneering California families. The couple settled in Santa Barbara, which led to Harmer being remembered as “Southern California’s first great painter of the 19th Century." At this time, his work revolved around a series of paintings of the Old California missions under Mexican rule. They resided on De La Guerra Plaza, which included the Adabie family home. From 1908 through the 1920s, Harmer established the first art colony on the West coast. Studios were added to the Spanish-Colonial adobe home of the Harmers, where many up and coming artists worked. Alexander Harmer died on January 10, 1925, supposedly while admiring the sunset from his backyard. This was just six months before the Santa Barbara earthquake, which left the Harmers' adobes in ruins. All four paintings are signed Alex. F. Harmer, but only two are dated. Below are photographs of the four paintings in the collection.